Congenital Abnormalities Gallbladder

The most common gallbladder injury due to blunt trauma is contusion; perforation and avulsion are rare. Only occasionally does CT reveal gallbladder wall disruption. A hematoma is identified by CT as focal or diffuse thickening, at times mimicking cholecystitis. Pericholecystic fluid, a poorly defined gallbladder wall, a collapsed gallbladder lumen, and intraluminal blood detected by imaging in a setting of abdominal trauma should suggest gallbladder injury.

Associated intraabdominal trauma is common, often masking underlying gallbladder perforation.

Associated intraabdominal trauma is common, often masking underlying gallbladder perforation.

Radiology images of Sedimentation of blood in gallbladder on T2–weighted MR image results in a hyperintense supernatant fluid.

This is Congenital Abnormalities Gallbladder

Agenesis of Gallbladder

Gallbladder agenesis is rare. An absent gallbladder is found in left-sided isomerism (asplenia). Most patients with gallbladder agenesis also have an absent cystic duct, and often other gastrointestinal anomalies are evident. An association exists between gallbladder agenesis and duodenal atresia. Some patients have symptoms clinically compatible with gallbladder disease and some even have a false-positive US study. Bile duct stones are relatively common in these patients. Gallbladder agenesis has only been diagnosed at laparoscopy for presumed cholecystitis in some of these patients.

Multiple Gallbladders

Most gallbladder duplications are discovered in a setting of either cholelithiasis or acute cholecystitis. Gallbladder duplication is more common in right-sided isomerism (polysplenia). Anecdotal reports describe not only stones in a duplicated gallbladder but also a carcinoma. Gallbladder duplication can usually be identified with US or any type of cholangiography. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also helpful in defining the underlying anatomy. Some double gallbladders are not detected either with preoperative imaging or even during cholecystectomy and a second operation is then necessary.

Multiseptate Gallbladder A congenital multiseptate gallbladder is rare. More common are gallbladder folds mimicking septa. Ultrasonography should detect a multiseptate gallbladder. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is helpful only if sufficientcontrast fills the gallbladder to outline the septa. These patients also have impaired gallbladder function.

Ectopic Gallbladder

An abnormal gallbladder location is more common than agenesis. Congenitally lax mesenteric attachments allow gallbladder migration to unusual sites. An ectopic gallbladder can be intrahepatic, extraperitoneal, in the lesser omentum, within the falciform ligament, or in other locations. It can be located just inferior to the right hemidiaphragm. Subcutaneous gallbladder herniation through the abdominal wall is rare. Also rare is internal gallbladder herniation through the adjacently located foramen of Winslow and obstruction to either bile or blood flow. Some patients also have associated hepatic lobe, portal vein, and pancreaticobiliary duct anomalies.

Imaging does not identify the gallbladder in its usual position. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is useful in defining this condition and identifying any associated ductal anomalies prior to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. With an intrahepatic gallbladder, Tc-99m– sulfur colloid scintigraphy reveals a focal intrahepatic defect.

Anomalous Bile Ducts Intrahepatic bile ducts develop from liver progenitor cells in contact with portal vein mesenchyme and form ductal plates that evolve into mature ducts. Failure of evolution leads to ductal plate malformation and congenital intrahepatic bile duct disorders characterized by dilated biliary segments and surrounding fibrosis.

Considerable variation exists in intrahepatic bile duct anatomy. A right lobe duct draining into the cystic duct, in particular, has bedeviled surgeons during apparent routine cholecystectomy. More complex intra- and extrahepatic bile duct anomalies are rare. One rather extreme example consists of the hepatic duct draining into the gallbladder and the cystic duct then draining the entire biliary system. Some preduodenal common bile ducts are associated with a preduodenal portal vein. These and other related anomalies need to be considered to prevent bile duct injury during cholecystectomy.

Computed tomographic cholangiography detects major bile duct anomalies. Both 2D and 3D images are necessary to fully evaluate these anomalies. Whether aberrant bile ducts are better identified by CT cholangiography or MRCP is detectable; the latter images are degraded by overlapping duodenum and other ductal structures.Complicating this issue is that MRCP rather than CT cholangiography has achieved a superior role as a preferred preoperative imaging modality.What preoperative role MRCP has in alerting the surgeon to possible bile duct anomalies and thus potentially decreasing intraoperative duct injury remains to be determined.

Gallbladder agenesis is rare. An absent gallbladder is found in left-sided isomerism (asplenia). Most patients with gallbladder agenesis also have an absent cystic duct, and often other gastrointestinal anomalies are evident. An association exists between gallbladder agenesis and duodenal atresia. Some patients have symptoms clinically compatible with gallbladder disease and some even have a false-positive US study. Bile duct stones are relatively common in these patients. Gallbladder agenesis has only been diagnosed at laparoscopy for presumed cholecystitis in some of these patients.

Multiple Gallbladders

Most gallbladder duplications are discovered in a setting of either cholelithiasis or acute cholecystitis. Gallbladder duplication is more common in right-sided isomerism (polysplenia). Anecdotal reports describe not only stones in a duplicated gallbladder but also a carcinoma. Gallbladder duplication can usually be identified with US or any type of cholangiography. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also helpful in defining the underlying anatomy. Some double gallbladders are not detected either with preoperative imaging or even during cholecystectomy and a second operation is then necessary.

Multiseptate Gallbladder A congenital multiseptate gallbladder is rare. More common are gallbladder folds mimicking septa. Ultrasonography should detect a multiseptate gallbladder. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is helpful only if sufficientcontrast fills the gallbladder to outline the septa. These patients also have impaired gallbladder function.

Ectopic Gallbladder

An abnormal gallbladder location is more common than agenesis. Congenitally lax mesenteric attachments allow gallbladder migration to unusual sites. An ectopic gallbladder can be intrahepatic, extraperitoneal, in the lesser omentum, within the falciform ligament, or in other locations. It can be located just inferior to the right hemidiaphragm. Subcutaneous gallbladder herniation through the abdominal wall is rare. Also rare is internal gallbladder herniation through the adjacently located foramen of Winslow and obstruction to either bile or blood flow. Some patients also have associated hepatic lobe, portal vein, and pancreaticobiliary duct anomalies.

Imaging does not identify the gallbladder in its usual position. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is useful in defining this condition and identifying any associated ductal anomalies prior to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. With an intrahepatic gallbladder, Tc-99m– sulfur colloid scintigraphy reveals a focal intrahepatic defect.

Anomalous Bile Ducts Intrahepatic bile ducts develop from liver progenitor cells in contact with portal vein mesenchyme and form ductal plates that evolve into mature ducts. Failure of evolution leads to ductal plate malformation and congenital intrahepatic bile duct disorders characterized by dilated biliary segments and surrounding fibrosis.

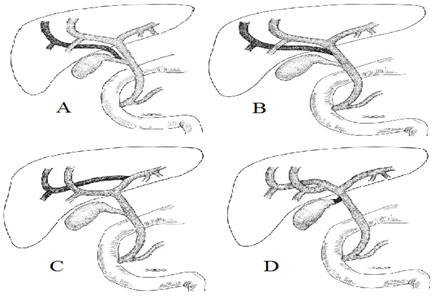

Considerable variation exists in intrahepatic bile duct anatomy. A right lobe duct draining into the cystic duct, in particular, has bedeviled surgeons during apparent routine cholecystectomy. More complex intra- and extrahepatic bile duct anomalies are rare. One rather extreme example consists of the hepatic duct draining into the gallbladder and the cystic duct then draining the entire biliary system. Some preduodenal common bile ducts are associated with a preduodenal portal vein. These and other related anomalies need to be considered to prevent bile duct injury during cholecystectomy.

Computed tomographic cholangiography detects major bile duct anomalies. Both 2D and 3D images are necessary to fully evaluate these anomalies. Whether aberrant bile ducts are better identified by CT cholangiography or MRCP is detectable; the latter images are degraded by overlapping duodenum and other ductal structures.Complicating this issue is that MRCP rather than CT cholangiography has achieved a superior role as a preferred preoperative imaging modality.What preoperative role MRCP has in alerting the surgeon to possible bile duct anomalies and thus potentially decreasing intraoperative duct injury remains to be determined.

This is radiology images Illustration of common bile duct anomalies. A: A right lobe branch inserts into the cystic duct. B: A right lobe branch inserts into the hepatic duct. C: A right lobe duct communicates with the main left lobe duct. D: A short cystic duct inserts close to the porta hepatis and the hepatic duct is very short. In such a setting the common bile duct is readily confused with the cystic duct.

Sphincter of Oddi Region Anomalies

Numerous anomalous biliary and pancreatic duct insertions are possible, including a long common channel (called anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary duct and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union by some authors). This latter congenital variant (depending on viewpoint, considered an anomaly, maljunction, or disease) consists of pancreatic and biliary duct union outside the duodenal wall. Such a long common pancreaticobiliary channel presumably leads to pancreatic juice reflux into bile ducts. Several patients with an anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction and pancreatic carcinoma have been reported. Whether such an association is fortuitous or not is conjecture.

The prevalence of an anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct connection is unknown.Anomalous insertions are associated with dilated bile ducts (choledochal cyst), a tendency toward gallstone formation, and possibly gallbladder adenomyomatosis. Even in childhood, anomalous pancreaticobiliary ducts are associated with increased gallbladder epithelial cellular proliferation, manifesting as epithelial hyperplasia. Ultrasonography, including endoscopic US, reveals a diffuse thickened hypoechoic inner gallbladder wall layer, indicative of mucosalhyperplasia; this characteristic sonographic finding of gallbladder mucosal hyperplasia is found only in those who have associated anomalous pancreaticobiliary ducts. An increased risk of gallbladder cancer has been suggested in affected patients.

Computed tomographic cholangiography is useful in evaluating pancreaticobiliary duct anomalous junctions; at times pancreatic juice is identified refluxing into the bile duct. The reverse is also true—in some patients contrast refluxes from the common bile duct into the pancreatic duct. Many of these maljunctions are readily identified with ERCP. Endoscopic US and intraductal US are helpful in defining surroundingstructures. An MRCP identifies an anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction in most patients, less so in children than in adults. Regardless of whether bile ducts are dilated or not, whether a prophylactic cholecystectomy should be recommended to patients with a pancreatic or biliary maljunction because of increased gallbladder cancer risk is not clear.

Numerous anomalous biliary and pancreatic duct insertions are possible, including a long common channel (called anomalous arrangement of the pancreaticobiliary duct and anomalous pancreaticobiliary ductal union by some authors). This latter congenital variant (depending on viewpoint, considered an anomaly, maljunction, or disease) consists of pancreatic and biliary duct union outside the duodenal wall. Such a long common pancreaticobiliary channel presumably leads to pancreatic juice reflux into bile ducts. Several patients with an anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction and pancreatic carcinoma have been reported. Whether such an association is fortuitous or not is conjecture.

The prevalence of an anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct connection is unknown.Anomalous insertions are associated with dilated bile ducts (choledochal cyst), a tendency toward gallstone formation, and possibly gallbladder adenomyomatosis. Even in childhood, anomalous pancreaticobiliary ducts are associated with increased gallbladder epithelial cellular proliferation, manifesting as epithelial hyperplasia. Ultrasonography, including endoscopic US, reveals a diffuse thickened hypoechoic inner gallbladder wall layer, indicative of mucosalhyperplasia; this characteristic sonographic finding of gallbladder mucosal hyperplasia is found only in those who have associated anomalous pancreaticobiliary ducts. An increased risk of gallbladder cancer has been suggested in affected patients.

Computed tomographic cholangiography is useful in evaluating pancreaticobiliary duct anomalous junctions; at times pancreatic juice is identified refluxing into the bile duct. The reverse is also true—in some patients contrast refluxes from the common bile duct into the pancreatic duct. Many of these maljunctions are readily identified with ERCP. Endoscopic US and intraductal US are helpful in defining surroundingstructures. An MRCP identifies an anomalous pancreaticobiliary duct junction in most patients, less so in children than in adults. Regardless of whether bile ducts are dilated or not, whether a prophylactic cholecystectomy should be recommended to patients with a pancreatic or biliary maljunction because of increased gallbladder cancer risk is not clear.

![image_thumb[1] image_thumb[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEj7Sf9oZ03E0M-QvBFJ5rCYu2WFGJk-TM3sweoLniyrJseXc2z-Q8H5ORcgi-nBtktJPtPmHuf8DbNWtW24kf2e0LEYP8NTDZLRvI2wuHoYaM6w6RR6n32FdR0aUHNQVwiOxJ1GnFFHDZE/?imgmax=800)

Post a Comment for "Congenital Abnormalities Gallbladder"