Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas

General

Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States and the incidence continues to increase in the Western world. It is more common in males. Typically, the cancer is discovered when it has already spread extensively. About two thirds of pancreatic carcinomas originate in the head of the pancreas. Jaundice is typically the initial presentation, and an enlarged, nontender gallbladder is often palpable (Courvoisier gallbladder). Occasionally, however, even a large pancreatic head tumor will not obstruct bile ducts. Duodenal obstruction initially is uncommon with a pancreatic head carcinoma, the exception being with a cancer developing in an annular pancreas, where duodenal obstruction is due directly to the cancer or, if the cancer develops in the adjacent pancreatic head, the obstruction is due to the surrounding pancreatitis. Pancreatic body and tail carcinomas present with pain and weight loss and generally extensive local invasion and metastases are already present when the tumor is first discovered.

Dull, almost constant visceral pain due to neural invasion is characteristic for these tumors.Malabsorption, steatorrhea, and weight loss ensue. Diabetes mellitus is quite common, but its etiology is puzzling. Pancreatic cancer patients show increased peripheral tissue resistance o insulin. Diabetes is an early manifestation, and long-standing diabetics are also at increased risk for pancreatic cancer. Surrounding focal pancreatitis is common, possibly a result of duct obstruction and rupture. An occasional patient presents with pancreatitis, even with acute recurrent pancreatitis. An association exists between deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary emboli, and pancreatic cancer. Date from the Danish Cancer Registry yields a cancer incidence ratio of 1.3 in these patients, but the risk is elevated only during the first 6 months and then declines to slightly above 1.0 at 1 year after thrombosis; of note is that distant metastases were already present in 40% of patients with a cancer detected within 1 year of thromboembolism. Various paraneoplastic syndromes are more common with an acinar cell origin carcinoma. An occasional pancreatic carcinoma is preceded by seborrheic keratosis (Leser-Trelat sign); skin lesions tend to diminish after resection, but progress with tumor recurrence.

Etiology Several risk factors are identified for pancreatic carcinoma. The relative risk of developing pancreatic cancer is about six times greater in patients who have had previous pancreatitis, with this risk beginning to increase 5 or more

years after a diagnosis of pancreatitis is established. This risk appears to be independent of sex, country, and type of pancreatitis. The initial data pointed to an association with cigarette smoking and coffee, but a Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and the Nurses’ Health Study, consisting of nearly two million person-years of follow-up and 288 pancreatic cancers, concluded that neither coffee nor alcohol increases the risk for pancreatic cancer. Likewise, if an association with a previous cholecystectomy exists, it is a modest one at best. An increased prevalence of gallstones, however, is found in those with pancreatic cancer. In rare families an autosomal-dominant predilection for pancreatic cancer appears to exist.

With an increase in life expectancy in patients with Hodgkin’s disease after chemotherapy and radiation, the development of a second malignancy is a well-recognized entity. Among these are reports of pancreatic cancer. An increased risk of pancreatic cancer appears to exist in patients with cystic fibrosis. Patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease are more prone to developing neuroendocrine pancreatic neoplasms than the average population, but not those of ductal origin.

Screening

Screening for pancreatic cancer is not widely practiced, and most tumors are not detected at an early tumor stage. Nevertheless, an abdominal US screening program in Japan achieved impressive results for detecting pancreatic cancer, reaching a sensitivity and specificity of 98% and 96%, respectively. Ideally, screening should detect a potentially curable cancer.A definition of high-risk groups is still evolving. Detection of K-ras mutations in endoscopically obtained pancreatic juice is applicable only to a high-risk group. Current technology suggests CT or US as a screening tool and, if either modality suggests a pancreatic carcinoma, then endoscopic US or MRCP should be done.

Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States and the incidence continues to increase in the Western world. It is more common in males. Typically, the cancer is discovered when it has already spread extensively. About two thirds of pancreatic carcinomas originate in the head of the pancreas. Jaundice is typically the initial presentation, and an enlarged, nontender gallbladder is often palpable (Courvoisier gallbladder). Occasionally, however, even a large pancreatic head tumor will not obstruct bile ducts. Duodenal obstruction initially is uncommon with a pancreatic head carcinoma, the exception being with a cancer developing in an annular pancreas, where duodenal obstruction is due directly to the cancer or, if the cancer develops in the adjacent pancreatic head, the obstruction is due to the surrounding pancreatitis. Pancreatic body and tail carcinomas present with pain and weight loss and generally extensive local invasion and metastases are already present when the tumor is first discovered.

Dull, almost constant visceral pain due to neural invasion is characteristic for these tumors.Malabsorption, steatorrhea, and weight loss ensue. Diabetes mellitus is quite common, but its etiology is puzzling. Pancreatic cancer patients show increased peripheral tissue resistance o insulin. Diabetes is an early manifestation, and long-standing diabetics are also at increased risk for pancreatic cancer. Surrounding focal pancreatitis is common, possibly a result of duct obstruction and rupture. An occasional patient presents with pancreatitis, even with acute recurrent pancreatitis. An association exists between deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary emboli, and pancreatic cancer. Date from the Danish Cancer Registry yields a cancer incidence ratio of 1.3 in these patients, but the risk is elevated only during the first 6 months and then declines to slightly above 1.0 at 1 year after thrombosis; of note is that distant metastases were already present in 40% of patients with a cancer detected within 1 year of thromboembolism. Various paraneoplastic syndromes are more common with an acinar cell origin carcinoma. An occasional pancreatic carcinoma is preceded by seborrheic keratosis (Leser-Trelat sign); skin lesions tend to diminish after resection, but progress with tumor recurrence.

Etiology Several risk factors are identified for pancreatic carcinoma. The relative risk of developing pancreatic cancer is about six times greater in patients who have had previous pancreatitis, with this risk beginning to increase 5 or more

years after a diagnosis of pancreatitis is established. This risk appears to be independent of sex, country, and type of pancreatitis. The initial data pointed to an association with cigarette smoking and coffee, but a Health Professionals Follow-Up Study and the Nurses’ Health Study, consisting of nearly two million person-years of follow-up and 288 pancreatic cancers, concluded that neither coffee nor alcohol increases the risk for pancreatic cancer. Likewise, if an association with a previous cholecystectomy exists, it is a modest one at best. An increased prevalence of gallstones, however, is found in those with pancreatic cancer. In rare families an autosomal-dominant predilection for pancreatic cancer appears to exist.

With an increase in life expectancy in patients with Hodgkin’s disease after chemotherapy and radiation, the development of a second malignancy is a well-recognized entity. Among these are reports of pancreatic cancer. An increased risk of pancreatic cancer appears to exist in patients with cystic fibrosis. Patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease are more prone to developing neuroendocrine pancreatic neoplasms than the average population, but not those of ductal origin.

Screening

Screening for pancreatic cancer is not widely practiced, and most tumors are not detected at an early tumor stage. Nevertheless, an abdominal US screening program in Japan achieved impressive results for detecting pancreatic cancer, reaching a sensitivity and specificity of 98% and 96%, respectively. Ideally, screening should detect a potentially curable cancer.A definition of high-risk groups is still evolving. Detection of K-ras mutations in endoscopically obtained pancreatic juice is applicable only to a high-risk group. Current technology suggests CT or US as a screening tool and, if either modality suggests a pancreatic carcinoma, then endoscopic US or MRCP should be done.

Serum Markers A number of tumor markers are available. Their current major diagnostic limitation is a lack of tumor specificity and, to a lesser extent, low sensitivity in detecting a pancreatic carcinoma. Serum levels of CA 19-9 appear useful in discriminating pancreatic cancer from benign disease, predicting resectability, survival rate after surgery, and as a marker for recurrence. The sensitivity of CA 19-9 levels in discriminating between benign and malignant disease was 85%; patients with a resectable tumor had CA 19-9 levels significantly lower than those with an unresectable tumor. After tumor resection, survival for those with CA 19-9 levels returning to normal was significantly longer than for those with CA 19-9 levels not normalizing. majority of postoperative patients developing a recurrence have increased CA 19- 9 levels. Nevertheless, false-positive CA 19-9 levels occur in pancreatitis, and the specificity of this test is low.

Pathology

Pancreatic adenocarcinomas are very aggressive tumors, and at the initial diagnosis either intrapancreatic metastases or multicentric tumor origin is common. A capsule is not evident. Often a desmoplastic reaction surrounds a tumor, making it appear larger. Either the main pancreatic duct or one of its secondary branches becomes obstructed early in the course, leading to duct dilation.A prominent histologic finding is early and extensive perineural invasion, believed to account for the persistent and severe pain associated with these tumors. Vascular invasion and spread to adjacent lymph nodes is also an early finding. Most pancreatic adenocarcinomas arise from pancreatic duct epithelium. A spectrum of changes ranging from ductal hyperplasia to carcinoma in situ are identified. Cancer variants include giant cell carcinoma, acinar cell adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, mucinous-type carcinoma, and probably some of the cystadenocarcinomas.A need for histopathologic diagnosis exists because about 10% of suspected pancreatic carcinomas are either not of ductal origin or not even malignant. Thus either a needle biopsy (or even cytology) or surgical biopsy is necessary.

Instead of ductal origin, an occasional neoplasm originates from pancreatic acinar cells; these include acinar cell adenocarcinomas and cystadenocarcinomas. An acinar cell adenocarcinoma is more common in elderly men and has an even worse prognosis than ductal ones. At initial presentation these tumors tend to be large and partly necrotic. For unknown reasons an occasional one is associated with subcutaneous fat necrosis. A rare carcinoma has both acinar and endocrine components. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma in children is either ductal or acinar in origin. Early metastasis is common.

These carcinomas involve activation of the Ki-ras oncogene, inactivation or mutation of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene, and dysregulation of growth factors. Additional tumorsuppression genes have been identified. Mutations in the p53 tumor-suppressor gene are present in up to 60% of solid pancreatic carcinomas. Pancreatic adenocarcinomas DNA also yield Ki-ras mutations in most patients. Kiras and p53 mutations are also identified in pancreatic juice from these patients, and such study may have a future role in early pancreatic cancer detection. Early Cancer No consensus exists for defining an early pancreatic cancer. Ideally, these should be cancers limited to duct epithelium. Follow-up of patients with tumor limited to the duct epithelium reveals a high 5-year survival rate, but these tumors are rarely detected. A review of small pancreatic cancers <2cm or stage I cancers (pooled from 15 publications) found 42% to be stage I and 58% to have no lymph node metastasis, and in almost all reports the 5-year postoperative survival rate was <50%; among pancreatic cancers 1 cm or less (pooled from three publications), 85% to 100% were stage I and the 5-year postoperative survival rate was 78% to 100%. Patients with 12 carcinoma-in-situ and intraductal carcinomas (pooled from four publications) were all stage I and were alive with no evidence of tumor recurrence for varying lengths of time.Based on these results, the authors propose that either pancreatic cancers <1 cm or in-situ and intraductal cancers with minimal invasion be defined as early pancreatic cancers. The problem of defining early cancer is illustrated by a 63-year-old man who had a CT for follow-up of rectal cancer,which revealed a pancreatic cyst in the head of the pancreas; ERP showed a narrowed main pancreatic duct in the body, and MRCP identified dilated ducts draining this region. Cancer cells were obtained by brushing cytology, and a total pancreatectomy was performed. Two sites of invasive carcinoma were identified in the neck and body, and there were multiple foci of severe dysplasia in the body of the pancreas,with some foci containing carcinoma in situ. The cystic tumor was an intraductal papillary adenoma.

Pathology

Pancreatic adenocarcinomas are very aggressive tumors, and at the initial diagnosis either intrapancreatic metastases or multicentric tumor origin is common. A capsule is not evident. Often a desmoplastic reaction surrounds a tumor, making it appear larger. Either the main pancreatic duct or one of its secondary branches becomes obstructed early in the course, leading to duct dilation.A prominent histologic finding is early and extensive perineural invasion, believed to account for the persistent and severe pain associated with these tumors. Vascular invasion and spread to adjacent lymph nodes is also an early finding. Most pancreatic adenocarcinomas arise from pancreatic duct epithelium. A spectrum of changes ranging from ductal hyperplasia to carcinoma in situ are identified. Cancer variants include giant cell carcinoma, acinar cell adenocarcinoma, adenosquamous carcinoma, mucinous-type carcinoma, and probably some of the cystadenocarcinomas.A need for histopathologic diagnosis exists because about 10% of suspected pancreatic carcinomas are either not of ductal origin or not even malignant. Thus either a needle biopsy (or even cytology) or surgical biopsy is necessary.

Instead of ductal origin, an occasional neoplasm originates from pancreatic acinar cells; these include acinar cell adenocarcinomas and cystadenocarcinomas. An acinar cell adenocarcinoma is more common in elderly men and has an even worse prognosis than ductal ones. At initial presentation these tumors tend to be large and partly necrotic. For unknown reasons an occasional one is associated with subcutaneous fat necrosis. A rare carcinoma has both acinar and endocrine components. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma in children is either ductal or acinar in origin. Early metastasis is common.

These carcinomas involve activation of the Ki-ras oncogene, inactivation or mutation of the p53 tumor-suppressor gene, and dysregulation of growth factors. Additional tumorsuppression genes have been identified. Mutations in the p53 tumor-suppressor gene are present in up to 60% of solid pancreatic carcinomas. Pancreatic adenocarcinomas DNA also yield Ki-ras mutations in most patients. Kiras and p53 mutations are also identified in pancreatic juice from these patients, and such study may have a future role in early pancreatic cancer detection. Early Cancer No consensus exists for defining an early pancreatic cancer. Ideally, these should be cancers limited to duct epithelium. Follow-up of patients with tumor limited to the duct epithelium reveals a high 5-year survival rate, but these tumors are rarely detected. A review of small pancreatic cancers <2cm or stage I cancers (pooled from 15 publications) found 42% to be stage I and 58% to have no lymph node metastasis, and in almost all reports the 5-year postoperative survival rate was <50%; among pancreatic cancers 1 cm or less (pooled from three publications), 85% to 100% were stage I and the 5-year postoperative survival rate was 78% to 100%. Patients with 12 carcinoma-in-situ and intraductal carcinomas (pooled from four publications) were all stage I and were alive with no evidence of tumor recurrence for varying lengths of time.Based on these results, the authors propose that either pancreatic cancers <1 cm or in-situ and intraductal cancers with minimal invasion be defined as early pancreatic cancers. The problem of defining early cancer is illustrated by a 63-year-old man who had a CT for follow-up of rectal cancer,which revealed a pancreatic cyst in the head of the pancreas; ERP showed a narrowed main pancreatic duct in the body, and MRCP identified dilated ducts draining this region. Cancer cells were obtained by brushing cytology, and a total pancreatectomy was performed. Two sites of invasive carcinoma were identified in the neck and body, and there were multiple foci of severe dysplasia in the body of the pancreas,with some foci containing carcinoma in situ. The cystic tumor was an intraductal papillary adenoma.

General Imaging Findings

A majority of pancreatic cancers present as focal tumors and thus only a portion of the pancreas is enlarged. It is the less common infiltrative variety that is difficult to identify. At times the only imaging finding is a subtle alteration in pancreatic gland outline. Especially when a tumor originates from the uncinate process, this finding is difficult to differentiate from normal,

keeping in mind that a pancreatic gland contour abnormality may be a normal variant, especially in the elderly. Distortion due to associated atrophy or pancreatitis is common. Pancreatic head cancers tend to obstruct both

the pancreatic and common bile ducts. If obstructed, the pancreatic duct dilates; duct dilation upstream of the tumor is occasionally the only finding detected by imaging, a finding also seen in chronic pancreatitis. An abrupt duct obstruction should raise suspicion for an underlying neoplasm; this finding is more common with a neoplasm than with chronic pancreatitis, where the entire pancreatic duct tends to be dilated. Even detection of a focal tumor is not pathognomonic; focal pancreatitis may have similar imaging findings. Most pancreatic cancers develop in a setting of a grossly normal pancreas, but with growth, surrounding pancreatitis is common and tends to obscure a tumor. The overall appearance is often also complicated by superimposed gland atrophy. At times a carcinoma in the body or tail is sufficiently large at initial presentation that it appears as an obvious necrotic tumor.

A majority of pancreatic cancers present as focal tumors and thus only a portion of the pancreas is enlarged. It is the less common infiltrative variety that is difficult to identify. At times the only imaging finding is a subtle alteration in pancreatic gland outline. Especially when a tumor originates from the uncinate process, this finding is difficult to differentiate from normal,

keeping in mind that a pancreatic gland contour abnormality may be a normal variant, especially in the elderly. Distortion due to associated atrophy or pancreatitis is common. Pancreatic head cancers tend to obstruct both

the pancreatic and common bile ducts. If obstructed, the pancreatic duct dilates; duct dilation upstream of the tumor is occasionally the only finding detected by imaging, a finding also seen in chronic pancreatitis. An abrupt duct obstruction should raise suspicion for an underlying neoplasm; this finding is more common with a neoplasm than with chronic pancreatitis, where the entire pancreatic duct tends to be dilated. Even detection of a focal tumor is not pathognomonic; focal pancreatitis may have similar imaging findings. Most pancreatic cancers develop in a setting of a grossly normal pancreas, but with growth, surrounding pancreatitis is common and tends to obscure a tumor. The overall appearance is often also complicated by superimposed gland atrophy. At times a carcinoma in the body or tail is sufficiently large at initial presentation that it appears as an obvious necrotic tumor.

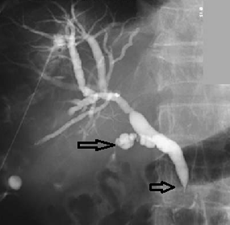

Radiology images An adenocarcinoma, probably of pancreatic origin, obstructs the common bile duct (arrowhead). The cystic duct is also infiltrated (arrow).

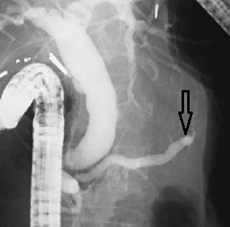

Radiology images of the pancreatic duct is obstructed (arrow) by a carcinoma in the pancreatic body

Radiology images carcinoma body of pancreas. Computed tomography reveals a large necrotic tumor (arrow).

Post a Comment for "Adenocarcinoma of the pancreas"