Hydatid cyst

Infection with Echinococcus granulosus, or hydatid disease, is uncommon in Northwestern Europe and North America but is endemic in the Mediterranean basin and several regions of East Africa. Dogs, ruminants, and humans constitute the infestation cycle. Most common ruminants involved are sheep and goats, although apparently camels also have a role in parts of Africa; the highest prevalence in humans is in the Turkana district of Kenya. Hydatid disease exists in cattle in West and Southern Africa but human infestation here is rare. The most common sites of involvement are the liver and lungs, the right lobe more often than the left, adjacent to Glisson’s capsule. Echinococcal cysts are slow growing and often take years to reach a large size.

Cysts contain two layers. The outer pericyst, composed of an avascular layer, is a host response to infestation. An inner endocyst, about 2mm in thickness, is produced by the parasite and normally is adjacent to the pericyst, except when ruptured. Although some cysts rupture spontaneously, especially when large, unrelated trauma is a not uncommon cause of cyst rupture. In a contained rupture only the endocyst ruptures, with thepericyst remaining intact. Some cysts rupture into an adjacent bile duct or directly into the peritoneal cavity, subphrenic space, or, rarely, into the gastrointestinal tract. Communication with a gas-containing viscus leads to a gas-fluid level within the cyst. Occasional cysts have transdiaphragmatic spread to the thorax. Rupture into a blood vessel, such as a hepatic vein, is rare.

Jaundice is usually due to cyst rupture into bile ducts and intrabiliary spread of the hydatid content. The resultant obstruction is generally treated by endoscopic sphincterotomy and removal of the obstructing intrabiliary daughter cysts. Occasionally, a hydatid cyst obstructs the bile ducts close to the liver hilum simply by compression, and jaundice develops even without a biliary communication. Likewise, a hydatid cyst close to the liver hilum can lead to cavernous portal vein transformation. In some patients hydatid cyst content in the bile ducts induces a hypersensitivity reaction, even to the point of anaphylaxis. A ruptured cyst is one cause of a relapsing generalized anaphylactic reaction, including life-threatening laryngospasm. An occasional one results in an eosinophilic cholecystitis.

The less common echinococcal infection with Echinococcus multilocularis is encountered in colder climates. Liver screening with US is practiced in some endemic regions, and screening appears to contribute to early detection. A local form of aggressive hydatid disease is found in Central and South American neotropical zones. The infectious agent is Echinococcus vogelii, paca, and other wild rodents are intermediate hosts, and the bush dog the final host. The liver is most often involved, with metacestodes spreading into the peritoneal cavity and eventually invading other abdominal and thoracic organs. Infected patients most often present with hard, round tumors in or adjacent to the liver, hepatomegaly, increased abdominal girth, pain, and cachexia; liver involvement progresses to portal hypertension. Imaging reveals a polycystic liver disease pattern. Extensive involvement leads to numerous cysts in the liver,

pancreas, spleen, and peritoneal cavity. Cyst calcifications are common.

An imaging classification of hydatid cysts consists of the following:

Cysts contain two layers. The outer pericyst, composed of an avascular layer, is a host response to infestation. An inner endocyst, about 2mm in thickness, is produced by the parasite and normally is adjacent to the pericyst, except when ruptured. Although some cysts rupture spontaneously, especially when large, unrelated trauma is a not uncommon cause of cyst rupture. In a contained rupture only the endocyst ruptures, with thepericyst remaining intact. Some cysts rupture into an adjacent bile duct or directly into the peritoneal cavity, subphrenic space, or, rarely, into the gastrointestinal tract. Communication with a gas-containing viscus leads to a gas-fluid level within the cyst. Occasional cysts have transdiaphragmatic spread to the thorax. Rupture into a blood vessel, such as a hepatic vein, is rare.

Jaundice is usually due to cyst rupture into bile ducts and intrabiliary spread of the hydatid content. The resultant obstruction is generally treated by endoscopic sphincterotomy and removal of the obstructing intrabiliary daughter cysts. Occasionally, a hydatid cyst obstructs the bile ducts close to the liver hilum simply by compression, and jaundice develops even without a biliary communication. Likewise, a hydatid cyst close to the liver hilum can lead to cavernous portal vein transformation. In some patients hydatid cyst content in the bile ducts induces a hypersensitivity reaction, even to the point of anaphylaxis. A ruptured cyst is one cause of a relapsing generalized anaphylactic reaction, including life-threatening laryngospasm. An occasional one results in an eosinophilic cholecystitis.

The less common echinococcal infection with Echinococcus multilocularis is encountered in colder climates. Liver screening with US is practiced in some endemic regions, and screening appears to contribute to early detection. A local form of aggressive hydatid disease is found in Central and South American neotropical zones. The infectious agent is Echinococcus vogelii, paca, and other wild rodents are intermediate hosts, and the bush dog the final host. The liver is most often involved, with metacestodes spreading into the peritoneal cavity and eventually invading other abdominal and thoracic organs. Infected patients most often present with hard, round tumors in or adjacent to the liver, hepatomegaly, increased abdominal girth, pain, and cachexia; liver involvement progresses to portal hypertension. Imaging reveals a polycystic liver disease pattern. Extensive involvement leads to numerous cysts in the liver,

pancreas, spleen, and peritoneal cavity. Cyst calcifications are common.

An imaging classification of hydatid cysts consists of the following:

Type 1: Simple unilocular cyst. Believed to be an early stage in hydatid cyst formation, these cysts are water dense on CT and anechoic on US. Cyst wall and septal enhancement is seen with CT and MR contrast, thus differentiating this entity from simple cysts.

Type 2: Cyst containing daughter cysts. Round or irregular daughter cysts are surrounded by a higher density fluid in the mother cyst.

Type 3: Dead cysts containing extensive calcifications.

Type 4: Complex cysts. These consist of superinfected cysts or ones that have ruptured. In a contained rupture imaging identifies endocyst separation from the surrounding pericyst. Bacterial superinfection implies the presence of cyst rupture. Curvilinear cyst rim calcifications are common with Echinococcus granulosus infections, and a cystic pattern is detected in about half.

Type 2: Cyst containing daughter cysts. Round or irregular daughter cysts are surrounded by a higher density fluid in the mother cyst.

Type 3: Dead cysts containing extensive calcifications.

Type 4: Complex cysts. These consist of superinfected cysts or ones that have ruptured. In a contained rupture imaging identifies endocyst separation from the surrounding pericyst. Bacterial superinfection implies the presence of cyst rupture. Curvilinear cyst rim calcifications are common with Echinococcus granulosus infections, and a cystic pattern is detected in about half.

The CT appearance varies, although a hydatid cyst tends to have an oval and sharply defined outline. Precontrast, cysts are mostly inhomogeneous and of low density; postcontrast enhancement is inhomogeneous. The sonographic appearance ranges from an anechoic cyst, mural nodules, and visualization of the endocyst, to a complex multicystic structure. Debris either tends to be displaced toward the center of the primary cyst or is located inthe dependent portion; or, in some cysts, a fluid–fluid interface is evident. A gas–fluid level within the cyst implies communication with bile duct or viscus, although occasionally an infected, noncommunicating cyst has a gas– fluid level. Detachment of the inner layer into the cyst lumen results in a soft tissue tumor either floating or in the most dependent portion of the cyst, an appearance termed the water lily sign.

Radiology images of Hydatid cyst. CT also identifies a soft-tissue component within the cyst (arrow).

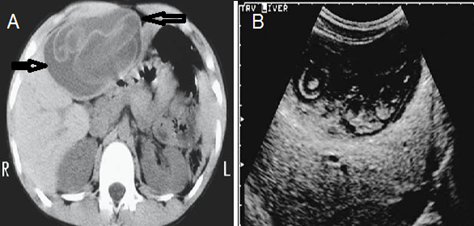

This is radiology images of Hydatid liver cyst in a 12-year-old. A: CT identifies a large cystic structure replacing most of the left lobe (arrows). A detached inner layer is seen floating in the cyst lumen. B: Ultrasonography (US) reveals an irregular cyst containing solid content (endocyst).

At times endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is helpful, although MR cholangiography also defines bile duct involvement. Cyst communication with bile ducts, bile duct obstruction, and debris in the bile ducts can be detected and, at times, treated by endoscopic sphincterotomy. Extensive publications confirm that ERCP is safe in a setting of hepatic echinococcosis. Magnetic resonance is useful in cyst characterization and in defining its relationship to the surrounding structures.Magnetic resonance imaging, MRA, and MR cholangiography should detect all hydatid cysts on both T1- and T2-weighted images and suggest a biliary communication. Angiography is rarely performed for suspected hydatid cysts. These are avascular, often multilocular cysts.

Radiology images of Echinococcal cyst communicating with bile ducts. Contrast partly outlines the cyst (arrow).

One should keep in mind that not all multilocular liver cysts are infectious in origin or even benign. The imaging appearances of an embryonal cell carcinoma or hepatobiliary cystadenoma mimic a hydatid cyst. With multiple hydatid cysts, liver parenchyma becomes sufficiently replaced that differentiation from polycystic disease becomes difficult.Infection with E. multilocularis results in somewhat different imaging findings. Irregular, necrotic liver lesions often mimic a neoplasm. Focal calcifications develop with both E. multilocularis and E. vogelii infections.

Radiology images of Echinococcus multilocularis presenting as multiple small foci scattered throughout the liver. It is hypointense on T1- (A) and hyperintense on T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (B). C: Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) outlines the cysts and bile ducts.

Post a Comment for "Hydatid cyst"